The most recent gathering of engineers and graduates from the Harbin Polytechnic Institute (HPI) and the Northern Manchurian University (NMU) has taken place at Sydney’s Russian Club. The world-class technical education given in Russian Harbin has allowed its graduates to achieve considerable success in later work in various countries around the world. The Russian engineers’ association, which has been active in Australia for many decades already, organises colleague and alumni gatherings each year.

Unification’s editor asked those present at the gathering to tell of the history of HPI and NMU.

President of the engineers’ association Victor Ignatenko:

“Over a hundred graduates would come to our traditional gatherings in past years. Twenty-five people, along with their spouses, came to today’s gathering. We’re marking three anniversaries at this gathering: the ninetieth anniversary of the Harbin Polytechnic Institute; so many years is just how old two of our friends, the association’s treasurer, Slava Baranovsky, and professor Mstislav Nosar, have turned, and this year Lyuba Gunko and I mark fifty-five years since the day we graduated from HPI. We turned out to be the Institute’s last Russian graduates; this was in 1958.”

“There are graduates from two institutions of higher education in your association: HPI and NMU.”

“These two educational institutions were connected to one another by historical events in Harbin. When Japanese authorities took away the opportunity for Russians to study at HPI, the University was opened, and the students who didn’t finish studying at HPI transferred to NMU.

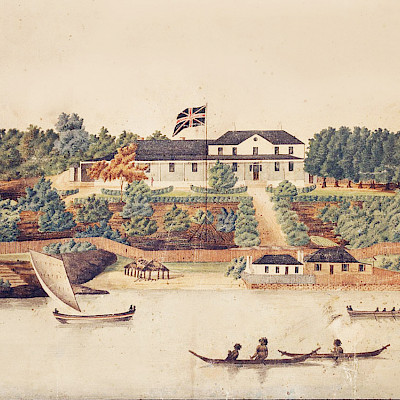

“It’ll be the right thing probably to tell of the history of HPI from the very beginning. A technical college was founded in Harbin in 1920, which was reorganised into the Sino-Russian Industrial University in 1922, where engineering personnel were trained for work on the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER). The professors there were highly qualified and were generally from Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Although studying there in general was very expensive, education was free for the students who were working on the CER. There were already over a thousand students, Russians and Chinese, studying here by 1930.

“The authority of HPI graduates who had graduated from there at the time was fully recognised all over the world. That’s how Kromalsky, an HPI graduate from those years who left for Sydney, became chief engineer at the central roads directorate in Sydney. The renowned scholar Leontovich, whose books I learnt from while studying at HPI, worked in America. There are a multitude of such examples I can give.

“In 1932, when Manchuria was taken by the Japanese army, the situation at HPI started to deteriorate. Japanese administrators started to manage the Institute completely in 1937, and teaching started to be conducted in Japanese. The Northern Manchurian University was opened in 1938 for Russian students, which NMU graduates Slava Baranovsky and Svetlana Kychakova will tell you more about.

“In 1945, after Soviet troops arrived in Harbin, HPI recommenced its work. New, experienced lecturers were recruited; many of them were lecturers from the Moscow Institute of Civil Engineering. Only six faculties were open here at this time, and HPI turned out over three thousand young engineers in 1949.

“After 1950 the CER was handed over to the Chinese government and renamed the CCR, the Chinese Changchun Railway. Many Russians started to leave Harbin. The number of Russian students at HPI started to decrease too, and the number of Chinese students grew. I graduated from the Institute in 1958; then there were only five Russian students left there. After graduating from the Institute, I married Lyudmila Gritsenko, a graduate from a medical assistant technical college, and we arrived in Australia in late 1961. Here I received the title of master’s degree holder, worked as an engineer at public organisations for many years, gave lectures at the University of Technology and published some scientific works.”

From the treasurer of the engineers’ association, Svyatoslav Baranovsky:

“I started studying at the Northern Manchurian University in 1941, which was located in Harbin, in a district named Novy Gorod. There were about five hundred Russian students studying here at this time. After successfully completing this course, I decided to continue studying and obtain a technical profession, so I found myself at the electromechanical department in 1944. With the arrival of Russian troops in 1945, the University set up by Japanese authorities was closed, and the Polytechnic Institute recommenced operations in 1946. My university classmate friends and I continued studying in our second year at HPI. I finished my railway engineering and construction course in 1951.

“I therefore ended up graduating from both educational institutions.

“Many started to leave Harbin at this time by now. Someone went to the Soviet Union, others went to Australia and America, and I arrived in Sydney in 1953, exactly sixty years ago. On day three I went out to work for the company BMC and transferred to BHP shortly after, where I spent about twenty years working for them. Over a hundred engineers who had graduated from institutions of higher education in Harbin found themselves in Sydney. Sadly, a large part of them are no longer with us: only about ten of them are left. I’m ninety years old, and the youngest among us is seventy-eight.”

Svetlana Danilovna Kychakova (Mikhaleva) studied at NMU and HPI as well:

“There were two faculties at the University: the commerce and polytechnic faculties. They didn’t admit girls to the polytechnic faculty then, so I started studying at the commerce faculty in 1943. With the arrival of the Red Army in 1945, the University was closed. We had already finished studying by this time, but we hadn’t managed to defend our degree theses. When HPI reopened, I went off to study at the transport economics faculty. In 1948 already, those who transferred from the University’s polytechnic faculty were defending their degree work, but I had to do an entire course, until 1950. That’s how I became a railway worker engineer.”

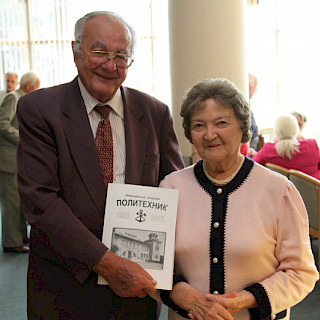

Fewer and fewer graduates are left, but the memories of the years studying at the Institute are not forgotten. Many events from those years are depicted in the Politekhnik journal published in Australia. Its editorial board released the journal’s seventeenth issue in Sydney last year. As the instalment’s editor, Victor Ignatenko, said, eight years have passed since the previous, sixteenth instalment was published. “It’s hard to anticipate the next journal’s release; after all, the youngest HPI graduates are over seventy-five years old. Forty-three years have passed since the first issue was released, in 1969.” The authors of the journal’s articles were not only engineers and graduates of HPI and NMU who found themselves in Australia, but also their colleagues living in America and Russia.

Graduates recalled their youth years, days spent in the student lecture halls, their professors, associate professors and departed friends at the gathering just before the new year in the Russian Club’s restaurant. Quite a few years have passed since the graduates’ time studying, but in their minds, it’s as if it were yesterday: a happy time that the engineers who were given an education in Harbin will remember for life.

Translated by Samuel Brotchie

Translator’s note

This translation is a translation of the original text and was completed by me in 2020 during my bachelor honours degree programme in the field of Russian.

I am not a professional translator and have no formal translation qualifications. Any mistakes in this translation should be considered in this context. Any views expressed in this translation are not a reflection of my views.

If any text in this translation contains text from external sources, this is indicated in this translation, and the details of these sources can be found in a list at the end of this translation.

I feel privileged to have had the opportunity to produce this translation, and I hope that it is of benefit to the literature on Harbin Russians and to the Unification community.

Samuel Brotchie

February 2021