The Dry Dock, a truly unique place is located on the South Bank of the Brisbane River. From the end of the nineteenth century to the early seventies of the twentieth century, vessels from all over the world came here for inspections and repairs. In our days, The Dock, that has become a historical item itself, houses the war river frigate Diamantina and the light ship Carpentaria. When you visit the Dock, you will easily spot a small schooner (lugger) painted red and white with the registration number A6, located on the left side of the historical object. This is the Penguin, a tangible evidence of the time, when the Pearl-shell fishing in the Coral Sea brought to Queensland profit, comparable to the export of the famous Australian beef.

Pearl fishing in Australia began long before the arrival of the first Europeans. Archaeological evidence proofs that Australian Aborigines were among the first people to appreciate the unique beauty of pearl-shells. The Aborigines of the Australian coast and the Torres Strait Islanders collected pearl oyster shells, which were abundant in the shallow waters, and traded them for other goods with the tribes, living inland. The stable trade links between the indigenous Australians are convincingly demonstrated by a fragment of a 22,000-year-old pearl-shell, found in the ancient rock settlement in the West Kimberley, located 200 kilometres from the coastline.

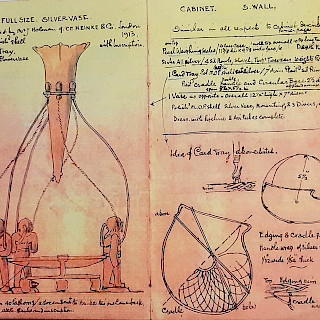

Pearling industry in the North of Queensland traces its history back to the first pearling luggers, built on Tutu (Warrior) Island in 1870. Within a few years, more than a hundred boats and luggers were drifting on the waters of the Torres Strait in search of precious shells. At the beginning of the twentieth century Japanese shipbuilders and divers arrived at Thursday Island which became the administrative centre of the Strait. The majority of them were from Wakayama Prefecture near the city of Osaka. Furuta Tsugitaro, who became one of the most famous shipwrights of the tropical state of Australia at that time, was one of them. Records in the British Register of Ships indicate that Furuta built none less than forty-one pearling luggers between 1899 and 1930. Penguin, built as Mercia, was launched in 1907.

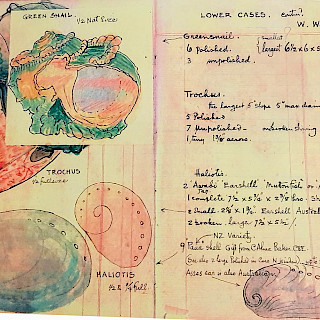

The owner of Mercia was Frederick Charles Hodels, the founder of a small pearling company Hodels Ltd, located on Thursday Island. Four years later, Hodels sold his business, including Mercia, to a larger enterprise Wyben Pearling Company Pty Ltd, which used the lugger to search for pearl-shells for thirty long years. Sea pearls and mother-of-pearl were supplied not only to mainland Australia, but also to Great Britain, America and Europe, where they were used for making jewellery, insets in furniture and cutlery set handles, ladies' hand fans, boxes and other lovely trinkets. But mother-of-pearl was mainly used for making buttons. Australian companies received huge orders for the supply of shells from world-famous haute couture houses.

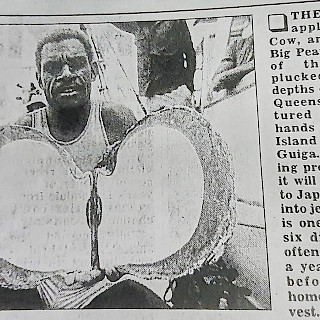

Work of pearl divers was hard and dangerous. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the oyster fields in the shallow waters off the coast of the Coral Sea had become significantly depleted, and to get the shells pearlers had to go further and dive much deeper. Hundreds of slowly moving ships were searching for precious pearl-shells on the underwater field, covering a huge area.

Each company owned a fleet of luggers, small vessels fifteen to twenty meters long, with low drafts, side ladders for divers and smoothly curved side lines. Sometimes a number of luggers in a fleet could reach twenty. Between the drifting luggers moved schooners, which were poetically called "motherships". They would collect caught shells on board and supply crews with everything they need.

Typically, a pearling lugger had a skipper, two divers, two or three tenders to operate the air pumps, an engineer, a cook and two sailing crew, usually Torres Strait Islanders. Their living and working conditions were far from comfortable. There was no toilet, to say nothing about a shower. Crew members slept below deck on a bed of palm leaves, cover themselves with thin cotton blankets. Meals were often cooked on an improvised barbecue; a sheet of steel attached to the engine exhaust pipe. The menu consisted of corned beef, caught turtles and dugongs and boiled mussels, served on rice. One had to get used to the smell of tons of shells, waiting on the deck for a mothership to be collected and taken to the island for sorting. But all these hardships were nothing compare to the danger that divers exposed themselves to every day, when plunging to the bottom of the Coral Sea in search of precious pearl-shells.

The divers, who were mostly Japanese, had to wear heavy rubberized canvas suits, boots laden with lead, each weighing 15 kilograms, and diving helmets with thick glass. Hardly moving along the deck in this equipment, they descended into the water along rope ladders to dive to the depths of more than seventy meters. There, underwater, their lives were in the hands of the tenders above, who operated the air pumps, delivering air through a long air hose, attached to the helmet of the diver. With the engines turned off, the luggers would slowly drift to avoid accidentally dragging the divers along the sea bottom. The heavy helmets restricted the divers' view, allowing them to look only ahead at a low angle. The pearl divers would scoop the shells into a bag on their chests, accumulating about twenty mollusks, weighing between twelve and fourteen kilograms in total. Every minute the divers spent on the oyster field was precious, because they got paid by the number of pearl-shells they found.

The main enemies of divers underwater were sharks. They not only attacked divers, but their fins also could get caught in the dive lines, which was very bad for the diver. Sometimes a diver, went in backwards along the side, would come face to face with a shark, waiting for him at the bottom of the ladder. He had to climb back super-fast, as best one could with the helmet, weighed twenty-five and a half kilograms, slowing a diver down. But decompression sickness, which took hundreds of lives, was more dangerous than sea predators.

When a diver returns to the surface from the great depth, undissolved gas from his lungs is released into the blood in the form of bubbles, causing the blood to foam and destroy the walls of blood vessel cells, that block blood flow. Except that, bubbles can penetrate into tissues and joints, which can lead to serious damage to nerve endings, internal organs and joints. When pearling lugger Mercia was launched at the beginning of the twentieth century, it had no engine and was equipped with a hand pump. By the mid-thirties, most ships were motorized and equipped with mechanical pumps, but compressors were hard to get. The only one decompression machine at the Thursday Island hospital could not significantly improve the situation.

After working for an hour on the seabed in a search for shells, the divers had to make a slow-staged return to the surface alone the main anchor chain. Typically, decompression time took two hours, but sometimes this was not enough. Arnie Duffield, who worked in the pearling industry for over thirty years, recalls: “If you had somebody coming up a line stage by stage, or had one already waiting on the line, another diver would go down to check, and would look at the eyes through the glass; if they were looking straight ahead it was alright. …but if you could see only the whites of his eyes, the man was likely to be lost. You could send them down again, to a depth of 30 feet (9 metres) using a supplementary anchor line, and they might wait there for more then a day, and be able to recover” (Arnie Duffield and Lee Duffield ‘Arnie: Pearls and Luggers in the Torres Strait’)

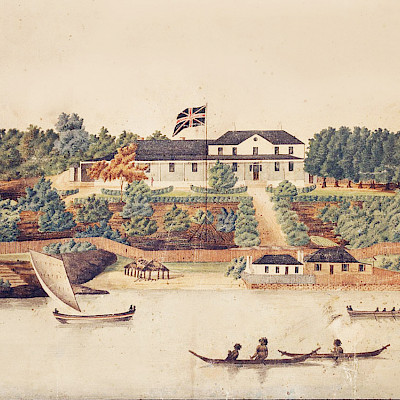

The hard, but peaceful and steady life of Torres Strait population, completely depended on the oyster-picking seasons, was interrupted by the Second World War. The main threat for the Pacific Region was militaristic Japan, who entered the war against the United States of America and the British Empire on December 8, 1941. Japanese forces attacked Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong, as well as the American naval base at Pearl Harbor on the island of Oahu, which was a part of the Hawaiian archipelago. The Japanese also aimed to occupy Tulagi, one of the Solomon Islands, and Port Moresby in New Guinea. The Japanese command planned to use these territories to establish military bases in order to invade New Caledonia, Fiji and Samoa and cut off supply lines and communications between Australia and the United States.

The evacuation of the population from the Torres Strait Islands began at the end of January 1942. The Japanese struck soon. At 12.25 PM on 14 March 1942, twelve Japanese Betty bombers and eight Zero fighters descended on Horn Island. For the next hour, the Japanese bombed and strafed the airstrip and its installations. It was the first attack on Queensland in the Second World War. When we say that 57 countries were involved in the bloodiest war of the twentieth century, with the total population exceeded 1.7 billion people (“World War II in figures and facts” - TASS special project tass.ru/spec/wwii), there is no exaggeration in our words.

All Wyben luggers, including Mercia, were requisitioned by the Commonwealth Government for military service in August 1942, as the islands of the Torres Strait became strategically very important. All the luggers pressed into military service underwent a conversion. Mercia’s conversion involved removing machinery and equipment associated with diving; stripping internal fittings, bunks, water tanks, etc.; removing ballast; lowering the cabin sole and increasing cargo space from 5–7 tons to 12–15 tons; making hatches and covers; surveying the hull; and undertaking general work on the rigging and windlass. The luggers, which became warships, were mainly used for patrolling the Torres Strait Islands and transporting supplies. Mercia also continued to work in the Torres Strait and north to New Guinea for several years. The Lugger was able to return to the shores of Thursday Island only at the beginning of 1946, after the end of the war.

The confiscation of the ships halted mother-of-pearl and pearl fishing for five years, allowing the pearl oyster population to recover. Prices for sea treasures skyrocketed, and the pearling industry started to rebuild. In 1948 Mercia was licensed to the Bowden Pearling Co. with the registration number A31, and served her new owners for a long thirteen years, until the company became bankrupt in 1961. Few years later Mercia acquired new owners and also a new name. She became the property of Aucher Pearling Shelling Company Pty Ltd. The lugger returned under the name Penguin, and its beautifully curved side bore the registration number A 61.

In the 1970s Penguin was again acquired by the Commonwealth Government and placed with the Dauan Island community in Torres Strait for use as a service and supply vessel. It was the way the lugger ended up at the most northern point of Australia’s territory, near the border with New Guinea. For more than ten years, Penguin delivered mail, food, and medicine not only to Dauan, but also to the other two islands – Boigu and Saibai, forming the north western island group of the Strait. Penguin connected lives of the inhabitants of the three islands, who considered themselves one people. Over the years of service, the Lugger became a member of the Doo-wan-an-gal family, the true owners of the land at the foot of Mount Cornwallis, which is part of the Great Dividing Range. When the time to replace the vessel with a more modern one came, the community agreed to hand it over to the Queensland Maritime Museum on condition that it retain its Dauan Island colours and number.

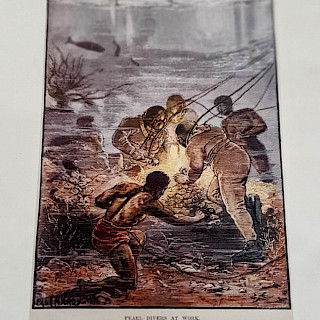

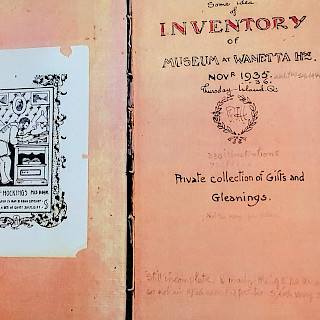

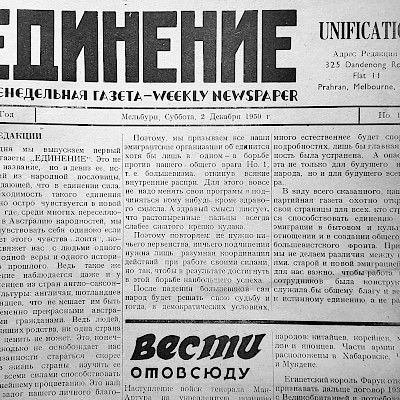

Penguin began her new life as a historical exhibit in 1982 and at the present time she is the only Queensland-built lugger in a museum collection. The other remaining boats, number no more than twenty that have survived the century, belong to private owners. Even though Japanese shipwright Furuta Tsugitaro built luggers out of hardwood, the sun and rains severely damaged the vessel hull. The Penguin restoration work started three years ago. One of the initiators of the project was John Hockings, for whom a small ship with a great history has special significance. John was born into a family of pearlers and spent his childhood in the Torres Strait Islands. John's relative Reginald Augustus Charles Hockings visited the small town of Kushimoto in Japan in 1910 to recruit divers for searching precious pearl-shells. When the pearler realised how poor the Japanese village was, he built and paid for the Shinozaki Elementary School for local children, which is still operating today. John Hockings' family also founded the Wanetta Museum on Thursday Island.

The volunteers, working under the leadership of shipwright Russell Cobine, started restoration on the port side of the hull, the area showing the worst signs of rot. More decay and damage were exposed as they slowly removed old waterproof sheeting from the deck, stripped paint from the hull and hammered out the concrete ballast. The restoration crew have done a tremendous amount of work for three years, but it is still far from been over. Once the restoration is complete, the vessel's deck will be refinished with Canadian Oregon timber, leaving the lugger looking exactly as it did 118 years ago. Project Managers plan to launch Penguin, giving museum visitors an opportunity to take boat trips along the River of Brisbane on the deck of the historic vessel that has served people for so long and faithfully.

I would like to express my deep gratitude to Queensland Maritime Museum volunteer John Hockings for providing photographs from his family archive.

Nataliya Samokhina

Brisbane