The relations of the Russians, the Chinese and a few other people.

A necessary preface

This article was written a long time ago, back in the 1990s, but was not published anywhere. At that difficult time, a great many people, to put it mildly, responded with hostility to everything associated with the USSR, with Russia. They didn’t even merely criticise it; rather, it was as if it had become “good form” to lambaste our country for and without a reason. At the time, I had read this newly written article of mine, and I of course had to include my chapter telling how Soviet authorities regarded Russian Harbin, which, in many respects, was not very well. But what’s done is done. However, joining the choir of ill-wishers and simply enemies of our country sickened me at the time, and therefore I decided not to publish my article. Now, however, the situation has fortunately changed. Russia, as they say, has got up off its knees, and I will no longer be uncomfortable with what I have written.

This article is a kind of postface to my article “Kharbin i kharbintsy” (Harbin and the Harbinites), which very briefly related what ethnic groups lived in Harbin and what the relations between them were like. Now we will recount these in somewhat more detail.

It should immediately be mentioned that during the first half of the 20th century, two main, separate communities, the Russians and the Chinese, existed in Harbin, although in the 1930s and the first half of the 1940s, a great many Japanese settlers lived in the city. At the same time, quite a few Koreans and people from certain other ethnic groups also lived in Harbin, but they more often attached themselves to the main communities mentioned above, which we will now discuss.

But first, let us discuss what the Russian community, Russian Harbin, was. For this, we shall use a quotation from my aforementioned article, “Kharbin i kharbintsy”:

“The Ethnic Composition of Russian Harbin:

‘Harbin Russians’ more or less reflected the ethnic composition of the European part of the Russian Empire. The overwhelming majority were russkie, i.e. all the rossy: Velikorossy, for the most part, and, to a lesser extent, Malorossy (Ukrainians) and Belarusians. The reason why they are combined into one group is also that the years of living together in Harbin did not preserve almost any distinctions between them.

Quite a few Poles, Armenians, Georgians, Jews, Tatars, etc., also lived in the city. They too did not forget their roots, establishing zemlyachestva 1* and clubs and building churches, synagogues and mosques. However, all of them were, so to speak, in keeping with Russian life and did not differ much from the other townspeople.

It would seem that interethnic friction and conflicts did not occur either, and the reason was not at all that some kind of unusually peaceable people lived in Harbin; rather, everyone simply felt a part of the same community. In other words, they were an islet of Russia in a vast Chinese sea, and no one thought that some single ethnic group had gained disproportionately large influence in the city.”

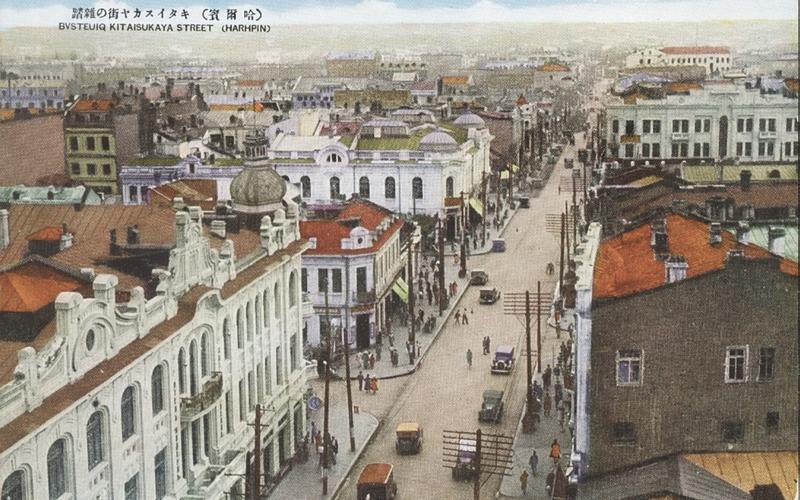

The Russian and the Chinese people of Harbin

Before the construction of the CER (Chinese Eastern Railway), there were few Chinese people in northern Manchuria. The land in general was half-empty. The site where Harbin was founded in 1898 had one or two small fishing villages and an abandoned baijiu distillery. There were still, so to speak, seasonal inhabitants there, since this practice was common: Chinese peasants from other provinces in China would rent a piece of land in the region, grow and gather in the crop there and then go home to repeat the whole process again for the following spring, but this time they probably did it on a different plot.

Many workers were needed when construction of the CER began; for hiring them, Chinese contractors were used, with whom they would conclude a contract for a certain amount of work. These contractors, in turn, would hire the workers in different regions of China and bring them to northern Manchuria. These people were mostly from the province of Shandong, which at the time was suffering from overpopulation, and that is why there was unemployment and terrible poverty there. Upon completing their work on the construction of the railway, many natives of Shandong would for a long time stay to live in Harbin and its environs. However, they did not forget about their hometowns.

I remember such an amusing episode. Somewhere in the year 1948 or 1949, when the Chinese Civil War was not quite over yet and it was still difficult to leave Harbin to go anywhere, our local Chinese shopkeeper suddenly announced that he was selling his shop and leaving . . . for Russia (!?). It was simply incredible. You see, Russia was the USSR at that time and was inaccessible to Harbin Russians, and suddenly a Chinese shopkeeper was going there?! When we asked him again whether it was true that he was leaving for Russia, his reply was yes, for Russia. Then we asked him, “And for which city?” His reply was “For Zhifu.” (This is the old name of the present city of Yantai in China’s Shandong province.) It turned out he had got the impression from conversations between Russians that Rodina (“home”) and Rossiya (“Russia”) were one and the same, synonyms. Therefore, instead of saying that he was going home, i.e. to Shandong in China, he said that he was going to Russia!

But, generally, everyone understands that the Chinese too, just like the Russians, lived in Harbin since the city’s very foundation. From the earliest years, the Harbin suburb of Fujiadian (Daowai) was settled almost exclusively by Chinese people, but in the city itself at first, there were few of them, mainly shopkeepers and various traders and contractors who served the Russian inhabitants. From that time, many Chinese people probably spoke and understood Russian, some quite decently; others, as they say, in “tvoya-moya”, 2* i.e. with shameless mispronunciation and through mixing up the cases and other grammar rules. For example, instead of Vy kupite pomidory? (“[Are you] buying tomatoes?”), you would hear them say Vasha pokupai pomidola? But the Russians understood them, and a similar situation was observed with the Russians: some learnt to speak Chinese, but many others knew only two or three dozen most commonly used words. Later on, as the economy developed and the region was opened up, (again, because of the CER!) the Chinese population increased exponentially, taking up residence now even in the city itself, and quite soon, there were far more Chinese people in Harbin than Russians.

From the very beginning, the Russians and the Chinese diverged only on what pertained to cultural life. This came about quite naturally, and there were no bans or restrictions. The Chinese had their own schools, theatres, newspapers, sports competitions, etc., and the Russians their own. Many other things, for example, shops, restaurants, transport, workplaces, recreational facilities, etc., were shared. Of course, the Russians and the Chinese differed in appearance too, which in itself contributed to diverging tendencies. It’s interesting to recall what the Russians and the Chinese called each other. The Chinese called the Russians lamouza 3* , which meant “shaggy cap”; this, according to legend, was what they once called the papakhas of the Cossacks from the CER guard troops. The Russians, in turn, also noticed an amusing manner of some of the Chinese on cold winter days: instead of wearing gloves or mittens, they would pull their freezing hands into the sleeves of their quilted anoraks; therefore, the shape of their bodies became like that of a penguin or a pheasant, and from this it become a custom to nickname the Chinese fazany (“pheasants”). There was nothing offensive about these nicknames, and, I think, the lamouzy and the fazany, as each was called, learnt to live peacefully side by side and formed mutually respectful relations between themselves. Even for all the last years of coexistence in Harbin, the Chinese called each and every Russian none other than sulyan lao-ta-ge, which translates as “Soviet big brother.” In any case, there was never a manifestation of the interethnic hostility that you often hear about now in news broadcasts: Indonesians looting Chinese people in Indonesia, Germans killing Turkish people in Germany or black citizens of the US and Britain stirring up real rebellion against their white fellow citizens. And not to mention the Palestinians and the Israelis.

So it’s not so with unexpectedness as it’s with simply human sadness to hear how in recent decades Harbin’s Chinese authorities have tried to wipe everything that was remindful of the city’s Russian origin off the face of the earth. (A reminder that this article was written in the 1990s. N. M.) These lines by the Harbin Russian poet Arseny Nesmelov therefore sound truly prophetic nowadays:

Dear town, proud and harmonious,

There will be such a day

When people will not remember that you were built

By a Russian hand. 4*

And one should like to hear how it would sound in the last lines of a poem by another émigré poet (Leri-Klochkovsky), just after replacing “French” with “Chinese”:

. . . . . .

The Chinese, having sent us their regards,

Will not gladly say, “They’re not here. . .”,

But gratefully say, “They were! . . .”

All in all, the Russian and the Chinese people of Harbin showed the world how such different people can live without any enmity, at least, without ethnically motivated enmity, and we can say that the overwhelming majority of Harbin Russians always showed fondness for and gratitude to the people of China. This was, for instance, what yet another Harbin Russian poet, Valery Pereleshin, did:

Nostal’giya (Nostalgia)

I shall not divide my heart into segments and slices;

Russia, Russia, my golden fatherland,

with a generous heart I love all the countries of the world,

But only you alone, my motherland, more than China!

I was raised at my tender stepmother’s, in a yellow country,

And gentle yellow people have become brothers to me;

Here I would imagine inimitable tales,

And the summer stars would shine for me in the night. 5*

The Russians and the Japanese

In 1932, for a long 13 years, the Japanese began their occupation of Manchuria and Harbin. Apart from the army, many Japanese settlers appeared in the city. They tried to live a life that was their own and shut out to others, barely mixing with either the Chinese or the Russians. In this way, three separate communities existed in Harbin in those days: the Russians, the Chinese and the Japanese. But, if the Russians and the Chinese lived in a jumble and kept normal working and good-neighbourly relations, then the Japanese tried to mass in titchy little mikroraiony 6* with their own separate shops, theatres, etc.; in other words, they lived their own, isolated existence. Unlike the Russians, who never demanded privileges, the Japanese enjoyed them in full. It reached a point where closer towards the end of the war, a direction came out by which only the Japanese were allowed to eat rice. This was particularly sore for the Chinese; after all, rice to them is what bread is to Russians.

Negative emotions definitely prevailed in the attitudes of Harbin Russians to the Japanese. There were the not quite healed wounds of the Russo-Japanese War, there was the natural reaction against the invaders, who strove to place everything under their command, and there was the outrage at the brazen inconsiderateness and cruelty of the Japanese militarists’ methods. They considered the Chinese as though they were not even human. They treated the Russians with more courtesy and more respect (also remembering 1905?), but undoubtedly considered both an obstacle in their plans. It must be recognised that some comparatively few Harbin Russians actively collaborated with the Japanese. Such people were always popping up when cities and countries were under the occupation of strangers, and Harbin was no exception. Some of them wanted to play with power over their own people; others probably acted in accordance with the guiding principle of Churchill’s, who after the conclusion of alliance with the USSR said that to save his country he was prepared to conclude an alliance even with the Devil himself.

The words of the head of the Japanese special service in Harbin, Colonel Asaoka, taken from the book by Japanese writer Seiichi Morimura Kukhnya d’yavola (The Devil’s Gluttony) (a book about the Kwantung Army’s infamous Unit 731, a Japanese centre for the development and conduct of biological warfare that was located in the settlement of Pingfang near Harbin and was where inhuman experiments on live humans were carried out), eloquently testify to the distrustful attitude of the Japanese authorities to Harbin Russians:

“. . . Harbin is a multiethnic city, and many tens of thousands of White Russian émigrés live in it. They are harbouring Soviet spies, and detecting them is not all that simple. Therefore, the gendarmerie has established a special agency, the Bureau for the Affairs of Russian Émigrés, in order to register every single Russian living in Manchuria and closely watch them. But there are so many of them that it is simply torture. . .”

I don’t know whether the Harbin Russians were harbouring a lot of Soviet spies, but they were a thorn in Japan’s side, that’s for sure. So a plan to resettle Russians from Harbin in the distant region of Toogen (which abuts the Amur and the Soviet border somewhere across from Blagoveshchensk) is hatched, and the first steps in this direction were being taken when a number of Russians, who were probably motivated by the still-burning spirit of the zemleprokhodets 7* - discoverers, went to live in Toogen. Before this, in order to popularise the resettlement, the authorities took these people along the streets of the city so that others could see the happy colonists; I remember the photographs of the procession in the newspaper the next day. I also remember too the persistent rumours about the desire or demand of the Japanese to erect their goddess Amaterasu in the Orthodox cathedral. This would have been so absurd that I now can’t even believe it. But at the time, serious grown-ups would also seriously discuss such a possibility. Nothing came of these fancies, in many respects because of the stable position of the Harbin Eparchy, in particular of that of Bishop Demetrius (Voznesensky), and soon the Japanese weren’t in the mood for doing this: they began to suffer failures on the front against the Americans, and the war swept with unstoppable force to the islands of Japan themselves.

Next came the Soviet Union’s entry into the war against Japan, and the defeat of Japan followed shortly after. Then, at the end of 1945, all of Harbin’s Japanese inhabitants were in the process of being repatriated to their home country.

In fact, there was yet another threat to the existence of Russian Harbin, and not only that of Russian Harbin. I somehow happened to read in an Australian newspaper that during the Korean War, General MacArthur, who was displeased with the entry of North Korean–sided Chinese volunteers into the war, insisted on and was allegedly close to implementing his plan to invade China and drop atomic bombs on major centres of Northeast China, including on Harbin, before the invasion. Later, the general thought of yet another plan: according to material from Russia’s Ministry of Defence published in the newspaper Krasnaya zvezda, MacArthur proposed scattering radioactive substances along the wide belt all along Korea’s border with China and thus isolate China from Korea for hundreds of years. I don’t know how much this all corresponds to the facts, since it wasn’t talked about very much. But if it’s true, then the people of Harbin should thank then US president Harry Truman, who, frightened of the consequences, dismissed MacArthur.

The Soviet Union and Russian Harbin

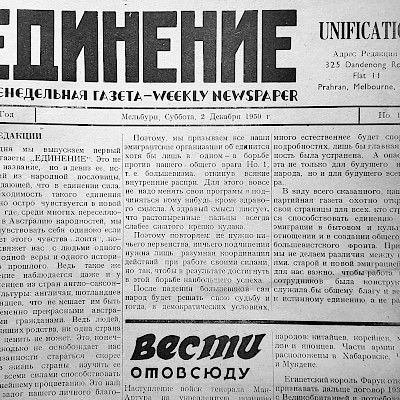

What did people in the USSR know about Harbin? Some individuals possibly would hear something about it, but everyone else was only able to find out about Harbin from publications intended for the general reading public, and the principle upon which these publications were written was that they contained either nothing or bad things about Harbin.

In the few things that were printed, there was a noticeable fixed cliché by which everything that was written had to conform to two basic tenets:

1. Harbin is the enemy centre of White Guard émigrés; and

2. the hopelessness of the émigré existence.

Let us look at some typical examples. This is from a Mariya Kolesnikova in her book about China Gadanie na ieroglifakh (Guesswork through characters), who even dedicated a whole five pages to Harbin:

“. . . signs, there were signs in Russian everywhere. They arrested attention above all. The street names were Russian too. . . . It made an extraordinary impression, a Russian city in the heart of Manchuria. Where did it come from and why? It’s funny but fact: Harbin would somehow remind me of Atkarsk, dear to my heart, and Saratov at the same time. . .

(Author’s note: These were, as they might say, the “good parts,” and then here were the “bad parts.”)

. . . there were no more than forty thousand Russians remaining, mainly members of the intelligentsia, who had settled there even before the revolution. Well, and the White Guards of course, all kinds of scum. . .

. . . An entire army of priests—Archbishops Meletius and Nestor, Bishops Demetrius and Juvenal and others—diligently waited upon the Japanese. . .

. . . Oh, my God! How complex human life is! Well, what is it to them, the Russians, this Harbin, a fleabag withdrawn into itself?! The miserable, hopeless existence of the eternal émigré. . .”

Here is another quotation, from the book by Soviet economist and sinologist Mikhail Iosifovich Sladkovsky Znakomstvo s Kitaem i kitaitsami (An acquaintance with China and the Chinese):

“. . . after the October Socialist Revolution in Russia, Harbin, as did the whole of northern Manchuria, became a refuge for the Russian counter-revolution, the White Guard armies of Ataman Semenov and General Kappel and various counter-revolutionary gangs fighting against Soviet Russia. . .”

Or we can take a look at the multi-volume work by Isaak Izrailevich Mints Istoriya Velikogo Oktyabrya (History of the Great October):

“. . . The representatives of the Entente countries vigilantly saw to it that the Soviet revolution did not cross Russia’s borders, in particular that it did not penetrate Manchuria and North China. Here they found the support of the capitalists and landowners who had been swept out from Russia’s boundary by the revolution and had flooded into Manchuria and North China. After settling in the towns and mainly the junctions of the CER, they expanded their active counter-revolutionary work. Harbin became a centre of anti-Soviet conspiracies and the forming of White Guard detachments. . .”

But it seems that everyone was outdone by Stalingrad hero Marshal Vasily Ivanovich Chuikov, whose contribution to the Stalingrad victory was truly great. In fact, he found himself in Stalingrad, according to a version by Western historians, as punishment for how at the very beginning of the Patriotic War, when the Soviet Union very much feared provoking Japan, he began to tell reporters from the newspapers as a military attaché in China how greatly the USSR was assisting China, which was at war with Japan. Chuikov himself mentions this only in passing, like a provocation, and about Harbin, where he stayed for a few days in the twenties, he writes in his memoirs as follows:

“. . . Harbin was the commercial and political centre of what was then Manchuria, its capital and at the same time its centre for smuggling and espionage activities. The whole city was a black market, where currency, narcotics, weapons and people were traded. Here, everything was considered a commodity. If something was not available, then it would be delivered from any corner of the globe. . . I was never again to encounter such moral decay as that of in 1920s Harbin. There were many Russians in the city, and not just émigrés. . . Their speech differed greatly from standard Russian both in accent and in vocabulary. . .” 8*

It remains unknown where and with whom the future marshal associated in Harbin; it would appear someone attempted to make an impression upon him with a varied cock and bull story, but he certainly shouldn’t have talked about speech. After all, many Harbin Russians at the time were very recent émigrés and still could not be in any way distinguished according to speech from Russians in Russia. Even much later, people coming from the USSR noted the Harbin Russians’ more correct Russian speech than that of theirs. Some compared it to Leningrad pronunciation; others declared that Harbin Russians spoke “like in the movies,” although everyone knows that actors pay a great deal of attention to the purity of their pronunciation. Even the vocabulary, if you don’t count slang words, of most Harbin Russians’ was, I believe, by no means lesser than that of the marshal’s. It’s a pity that he didn’t live to see the present day, to see today’s Moscow of the ’90s—without leaving his flat he could have even watched the programmes on Moscow television and marvelled at the “moral decay” 9* in the country.

Things were even worse with human relations in so far as they were almost unobserved. In the ’40s and ’50s, Harbin was where many people visiting on business from the USSR lived: railway workers and various other specialist workers who were helping China rebuild its economy. They were forbidden to mix with the local Russians. Many signs indicated that they themselves would have willingly mixed with the local Russians, but, evidently, they were afraid of losing what was for them very “profitable” work. This kind of apartheid sometimes led to absurd situations. People would tell of one Soviet specialist worker who was required to go somewhere; he didn’t know the town and began asking for directions from people passing by. There were no fewer Harbin Russians around than there were Chinese people, but he only spoke to the Chinese people, and what’s more in Russian, and they shrugged their shoulders and said pumimbai, i.e. “I don’t understand.” Finally, in desperation, he went up to a Russian, who said to him with his thick Russian accent pu-mim-bai. It would have been good if situations like these didn’t happen, of course, but one can understand this person.

Another large group of people from the USSR who were in Harbin at that time consisted of people who were known as the letchiki (“aviators”) (pilots, mechanics, navigators, etc.) and were giving the Chinese access to aircraft. The football fans among them organised their own team, naming it Avangard, and began taking part in the Russian Harbin second-division championship. It looked as if some interaction with the local folk was supposed to begin. But their team would usually arrive by bus almost exactly at the start of their match and, already dressed in their sports uniforms, played their game before quickly driving off home without changing. Even if they sometimes stayed to watch a game, then they would always stay only in their own group and cheer loudly in an emphatic manner for any Chinese team playing against any Russian one. It was funny but unpleasant.

However, only a few years before this, in 1945, the Harbin Russians’ relations with other Soviet soldiers took a different shape. They were welcomed as the liberators from the Japanese and like relatives: people would invite them into their homes and try to do something nice for them, and the soldiers would respond in kind.

One of my most vivid impressions of that time, for ever etched on my memory, was the Victory Day Parade by the Red Army units in Harbin in 1945 (the sole Victory over Japan Day Parade took place on Stalin’s orders only in Harbin, on 16 September 1945) or, to be more exact, how the people of Harbin received the marching soldiers. People filled all the pavements of the streets along which the parade went. It seemed all the city’s inhabitants had come out, festively dressed and very excited. They had dreamt of seeing Russian soldiers on the streets of their city for such a long time that now, when it happened, when these warriors were passing by so closely that you could touch the gold shoulder straps of the officers’ (these shoulder straps, like those of the old Russian army, made the greatest impression on many Harbin Russians), people cried out warm, cordial things in a kind of spontaneous fit, barely suppressing the emotions that filled them, almost like in a trance, and flowers flew to the feet of the soldiers. I, a little eight-year-old boy, was standing with my mother right in the middle of the triumphant people, and because of my small stature I saw the faces of the Harbinites standing around us more than the soldiers passing by. For me, it was a revelation to see grown-ups weeping for joy and feeling not at all embarrassed around others while doing so.

The previously mentioned Soviet writer Kolesnikova remembered those days as follows:

“. . . detachments of our sailors passed along the streets of the city to the thunderous ovations of the Russians and the Chinese: they stepped round the bouquets of flowers, young Russian women and men ecstatically embraced them, and little old ladies made the sign of the cross. . .”

Then it was the NKVD–SMERSH that arrived in combat army transport, but we’ll discuss this a little later. Let’s just say that at that time already, someone didn’t like the combat soldiers’ and officers’ cordial relations with the Harbin Russians. I recently read a narrative by the good Russian writer Boris Mozhaev, Izgoi (The Outcast); it was interesting to find this passage in it:

“. . . in those days (1946–50, N. M.), passage by rail from Vladivostok to Port Arthur via Harbin was closed: the watchful authorities were protecting the officers from the corrupting contact with the White Russian émigré public and the Cossacks living in the city and its environs. Later, during the Korean War, when the shipping routes were cut off, arrangements were made to construct a bypass around Harbin; the journey was awful, and the carriages would get jolted and rocked slightly, which is why skirting the city was slow and took a long time. Pressing themselves to the windows, the passengers marvelled at the Russian villages drifting by with their long straight streets forming opposite rows of houses: the houses were painted with ochre and red lead and had fretted casings, jambs and lintels, pale blue shutters and even roosters carved out of tinplate that were nailed at the very tops. . .”

Whyever was there this attitude, one that bordered on paranoia, to all the Harbin Russians? Meanwhile they, the Harbin Russians, were always different with regard to the USSR. After all, it was possible to find chapters of the city’s history revealing a different, so to speak, not a “White Guard” side to Harbin. Examples of these were the “revolutionary struggle of the CER workers” or any of the achievements of Harbin’s Soviet citizens in the 1920s–30s. True, at the beginning of the 1920s something about the revolutionary struggle did appear in the historical literature, but this then ceased. Why? The explanation was quite simple: almost all the Harbin Russian revolutionaries and merely Soviet citizens later found themselves in the camp of the notorious declared “enemies of the people.”

But there was another explanation nevertheless. After all, however could one write about the revolutionary struggle of Harbin’s workers without having mentioned that in 1917 the Harbin Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies (HSWSD), which for a short time even seized power in Harbin (it was a unique event in history when these Russian revolutionaries proclaimed Soviet rule in the territory of a foreign state), was being headed by the rather famous Martemyan Ryutin, the same Ryutin who at the end of the 1920s as one of the party bosses in Moscow and as a member of the CC AUCP (B) (Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party [of Bolsheviks]) with a then great many supporters came out against Stalin’s policies with his “Platform,” as it has been called, but failed? Meanwhile, the leader 10* deprived his conquered opponents not only of their existence but also deprived the population of memory of them.

Perhaps that’s why only historians and not the general public also knew about Ryutin’s Harbin comrade-in-arms Alexei Lutsky, who in 1920, long before the party strife, was incinerated by the Japanese in a steam locomotive firebox along with Sergei Lazo and Sibirtsev. After all, what a lot of so-called heroics one could make up about the Bolshevik royal army captain Lutsky, who served as head of the CER right-of-way zone’s counterintelligence and placed all this counterintelligence work at the service of the Soviet regime! It could have worked out better than the adventures of Stierlitz (Isaev). An interesting fact as well: the Bolshevik Lutsky was head of the CER right-of-way zone’s counterintelligence even when it was Admiral Kolchak who was commander of the CER guard troops.

Can one write about the many thousands of Soviet citizens, mainly railway workers, without having said what happened soon after their arrival in the USSR in 1935? About their almost universal arrest?

So it remained to write about only the so-called centre of the White Guards. Incidentally, the names of many White leaders are, in one way or another, indeed associated with Harbin: before leading the White movement, Admiral Kolchak, as was already just mentioned, commanded the CER guard troops and lived in Harbin; his associate General Kappel was buried within the railings of Harbin’s Iveron Icon Church (the general was recently reinterred at the Donskoe Cemetery in Moscow); and Ataman Semenov, although he lived in Dalny (Dairen), often visited Harbin too. Even long before the civil war, future generals Lavr Kornilov and Anton Denikin served in the CER guard troops. (Captain Denikin, admittedly, was quartered not in Harbin itself but at Hengdaohezi 11* station.) Even one of the members of the Provisional Government, Alexander Guchkov, also once served at the same place.

I would often hear questions of surprise, especially from foreigners: why did many Harbin Russians not go home to the motherland but ended up abroad? However, one ought to be surprised at a different thing: why did so many Harbin Russians, in spite of the open hostility of the Soviet authorities to themselves, still go to the USSR? After all, it was clear that for these authorities, any Harbin Russians were a foreign element. Perhaps I’m mistaken about something, generalising too much, but let us recall once more how everything happened.

In the ’30s, Soviet authorities intercepted all Soviet Harbin Russians, who had faithfully served the Soviet Union and had voluntarily gone there. In 1945, after the Red Army’s arrival in Manchuria, the arrests were so overdone that it seemed a little more time and all the Harbin Russians would be moved to the gulags, as they call them. Here, not at all trying to excuse the NKVD workers, I ask you, the reader, to understand their position: it was said over and over again so much and for such a long time that Harbin was a nest of White Guards and other antisovietists, and if they arrest only a handful of those who really deserved to be arrested, then simply they themselves could end up behind the barbed wire for negligence! And so, to meet the certain arrest quota proportionate to a city’s reputation like that of Harbin’s, they began to seize many people who were completely innocent . . . I don’t know how many people were arrested, probably many thousands; I remember only that a great many of my peers were left without their fathers. Later, everyone who had been seized then was rehabilitated after Stalin’s death, but how can one atone for the lives destroyed, the years of suffering and the health lost?

In 1946, almost all Harbin Russians became citizens of the USSR, and when the certain newly made Soviet citizens conceived the idea of going to live in the USSR, they were given a brief explanation: even without them, the people in the Soviet Union had enough of their own belobandity (“White bandits”). It’s interesting too that elections to the Supreme Soviet, which were always held in the USSR with pomp and festivities and were compulsory for everyone, were held for the new Harbin Russian citizens only once; then, these too were probably considered unnecessary (although maybe they were in fact right about this?!).

Furthermore, a worrying sign came in the form of an explicit ban on interaction between visitors sent on business trips from the USSR on one side and Harbin Russians on the other, despite the fact that they were all citizens of the same country. And, of course, the last straw had to have come in the form of the half-mocking permission in 1954 to leave for the homeland—only to the virgin lands, only to where they were taking you, and to where indeed. For some reason they kept it a secret, so some of those who were leaving thought that they were going to Altai but ended up in the semi-deserts of Kazakhstan. It is significant that the regions in the virgin lands where Harbin Russians were unloaded mainly contained former political prisoners released not long before. I remember when one of my friends who had gone there wrote in a letter that they had former prisoners living around them; I didn’t understand at the time and felt sorry for him, that he was living near thieves and bandits.

Nevertheless, in Harbin the following year of 1955, people were again recruited for the virgin lands, and again many people left: to the same place, in the same way and under the same conditions. At this point, it would be appropriate to give the floor to a direct participant in those events: a young Harbin Russian, who strove with sincere joy and enthusiasm for an encounter with the homeland and left for the virgin lands after finishing school in 1955. She describes her impressions of this encounter in a letter:

“. . . so then our special train started; no one knew where and when we were arriving. People asked us at the main stations, ‘Where are you going? Recruits or something?’ One eccentric clutched his belly at our reply that we were going voluntarily to the virgin lands and said, ‘Ha ha ha! I hadn’t laughed in ten years, but you’ve made me laugh: I’ve never seen such fools who would go as volunteers!’

All these remarks and questions were dismaying. It was horrifying what we saw: poverty, children begging for some bread, and the terrible foul language from workers repairing our carriages at the main stations. . .

Finally, on 13 June we arrived at our journey’s terminus: Bulaevo station, North Kazakhstan Region. We were again loaded somewhere, this time onto dusty trucks, and after two hours’ drive we arrived at the central farmstead of the vast Sovetsky sovkhoz.

We were met by a few dozen houses occupied by many Germans, Armenians and people of other ethnic groups who had been subjected to repression. Apart from the houses that had been rendered habitable, there were unfinished ones, where we were moved into, a few families into each. We were shoved into a single room of eight people, and all our things were outside. The sovkhoz inhabitants greeted us with the words ‘The next group of exiles has arrived.’ Spirits were not bright, and that’s not all.

The most awful thing was the fact that there was no drinking water. Water was fetched from a marsh, where geese swam and cows drank. The water was yellow and stank, and bugs and tadpoles swam around in it. We would go for the water on oxen yoked to a telega with a cask that had ‘MU-2’ written on it. At home, the water was filtered and boiled; then we added citric acid and, holding our noses, drank it with difficulty. . .”

Yes, indeed, the most natural thing for a human being is to live among one’s people: one’s family and one’s nation, but worst of all is when “your” people regard you as a stranger. So it’s not surprising that a portion of Harbin Russians ended up abroad, not in the motherland, and they were driven not by the fact that Soviet stores didn’t have much kolbasa but by much more serious motives. Much in the USSR seemed to be going against traditions that had developed over centuries.

Religious people were subjected to persecution as though they were engaging in subversive anti-state activities, although Orthodoxy and especially Orthodox ethics had always been the foundation upon which the lives of Russian people were built. And if it were not compulsory to always and fully agree with the party line in the USSR for a normal human life but to serve their country simply to the best of their abilities and capacity without breaking national and moral laws, then none of the Harbin Russians probably would have gone abroad.

As a matter of fact, the party monopoly on truth and power did a disservice to the Soviet Union and the CPSU itself. Indeed, this monopoly is what even current communists themselves call one of the main causes of the country’s incredibly fast disintegration between 1989 and 1991 (from a speech by CPRF leader Gennady Zyuganov – Nash sovremennik, no. 11, 1997, p. 13). The great power was being torn down, to the delight of Russia’s enemies, by then communists themselves, and, again in truly communist fashion,

“. . . we will raze this world of violence down to the ground, and then. . .”*12 by all means none other than down to the ground again! Nevertheless, far from everything in the USSR was bad . . . but that’s quite another subject.

In conclusion

People have had to hear time and again that for many decades our homeland treated the Harbin Russians like unloved stepchildren. But our homeland is not just a country in some narrow period of time and, of course, is not the chance people in Russia who found themselves in power in 1917, but is a millennium-old Russia, and Russian people, wherever they live, whether in Harbin or in Russia, represent only a small part of this millennium-old Russia with common ancestors, traditions and history. The Harbin Russians always remained faithful and never lost the spiritual connection with exactly this historical homeland of theirs, even if the Soviet regime did try to separate them from Russia.

Russian Harbin existed for some sixty years. This is an insignificantly short period of time in the history of any city, even shorter than the average human life, and is at first glance inadequate for the formation of certain stable traditions and everything that people call the character and soul of the city and that, through invisible bonds, firmly ties people to it. But talk with former Harbin Russians and you will see that this city in China’s northeast that is seemingly not gifted with special beauties remains for ever in their hearts. They dedicate poems and songs to it; their most pleasant memories are associated with it. As the Harbin Russian poet Elena Nedelskaya wrote:

“. . . I have seen beautiful cities, but you, my dusty town, are more dear than all.”

And so Russian Harbin is no more, but its history, after long years of hushing up or incomplete, non-objective treatment, is now more and more frequently attracting the attention of various researchers. And yet this is, as they say, in dribs and drabs. A complete comprehensive history of the city on the Sungari still awaits its Klyuchevskys and Karamzins.

Nikolai Mezin

Sydney, Australia

Translated by Samuel Brotchie

1 Singular form: zemlyachestvo

2 «‘Tvoia-moia’" is the name of the pidgin language that was used in Harbin («From the editors," 2019, pp. 9–10).

3 All words that have evidently been transliterated from Chinese into Russian in the original article have been transliterated from Russian into English here.

4 I drew from comments made in Meng Li (2004, p. 490) for translating these lines of poetry.

5 My translation of Nostal’giya (Nostalgia) contains elements that were taken from and elements that are similar to elements in Bakich (2015, p. 88), Pereleshin (1943, as cited in Bakich, 2015, p. 88), Xinmei Li (2016, pp. 298–299) and Meng Li (2004, p. 489).

6 Singular form: mikroraion

7 Землепроходец (zemleprokhodets) is defined as «старинное название русского путешественника, открывавшего, исследовавшего и осваивавшего неизвестные до той поры земли Сибири и Дальнего Востока» [old name for a Russian traveller who discovered, explored and settled till that time unknown lands of Siberia and the Far East] (Zemleprokhodets [Zemleprokhodets], 2014, Zemleprokhodets [Zemleprokhodets] section).

8 My translation of this passage of excerpts contains elements that were taken from and elements that are similar to elements in Chuikov (1981/2004, p. 7).

9 Moral decay is derived from the translated passage of excerpts addressed in footnote 8.

10 I believe that leader here refers to Stalin.

11 I have used a transliteration of this station’s name based on popular usage.

This article cites material from the following publications:

Mikhail Iosifovich Sladkovskii, Znakomstvo s Kitaem i kitaitsami (An acquaintance with China and the Chinese).

Mysl’, Moscow, 1984.

Gennadii Ivanovich Andreev, Revolyutsionnoe dvizhenie na KVZhD v 1917—1922 gg. (The revolutionary movement on the CER from 1917 to 1922).

— Nauka, Sibirskoe otdelenie, Novosibirsk, 1983.

Seiichi Morimura, Kukhnya d’yavola (English title: The Devil’s Gluttony). Translated from the Japanese by Svyatoslav Vital’evich Neverov.

— Progress, Moscow, 1983.

Mariya Kolesnikova, Gadanie na ieroglifakh (Guesswork through characters).

— Sovetskii pisatel’, Moscow, 1986.

Isaak Izrailevich Mints, Istoriya Velikogo Oktyabrya (History of the Great October), volume 3. 1973.

Marshal Vasilii Ivanovich Chuikov, Missiya v Kitae (English title: Mission to China: Memoirs of a Soviet Military Adviser to Chiang Kaishek).

— Voennoe izdatel’stvo Ministerstva Oborony SSSR, Moscow, 1983.

Boris Mozhaev, Izgoi (English title: The Outcast).

— Nash sovremennik, no. 3, 1993.

Anton Ivanovich Denikin, Put’ russkogo ofitsera (English title: The Career of a Tsarist Officer: Memoirs, 1872–1916).

— Izdatel’stvo imeni Chekhova, New York, 1953.

Harbin’s Soviet Secondary School No. 2 (Vtoraya Sovetskaya srednyaya shkola; 2 SSSh; 2SSSh) graduates of 1955 anthology Ostavaites’, druz’ya, molodymi! (Friends, stay young!).

— Published in Sydney in 1997.

Russkie kharbintsy v Avstralii №2 (Harbin Russians in Australia no. 2). Anniversary anthology, 2000. Supplement to the journal Avstraliada (English title: Australiada).

This article also used material from the Australian newspapers The National Times and The Sun and other publications and also

The historian Konstantin Asmolov: “Neokonchennaya voina” (The unfinished war) (in Korea)

https://lenta.ru/articles/2015/09/26/korea/

Translator’s note

This translation is a translation of the original text and was completed by me in 2020 during my bachelor honours degree programme in the field of Russian.

I am not a professional translator and have no formal translation qualifications. Any mistakes in this translation should be considered in this context. Any views expressed in this translation are not a reflection of my views.

If any text in this translation contains text from external sources, this is indicated in this translation, and the details of these sources can be found in a list at the end of this translation.

I feel privileged to have had the opportunity to produce this translation, and I hope that it is of benefit to the literature on Harbin Russians and to the Unification community.

Samuel Brotchie

February 2021

__________________________________________________________________________________

List of external sources used in this translation

Bakich, O. (2015). Valerii Pereleshin: Life of a silkworm. University of Toronto Press. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/10.3138/9781442619036

Chuikov, V. I. (2004). Mission to China: Memoirs of a Soviet military adviser to Chiang Kaishek (D. P. Barrett, Ed. & Trans.). EastBridge. (Original work published 1981). https://books.google.com.au/books?id=x_FwAAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s

From the editors: Historicizing the social contract. (2019). Ab Imperio, 2019(3), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2019.0062

The Internationale. (2020, September 2). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Internationale&oldid=976306607

Li, M. (2004). Russian émigré literature in China: A missing link (Publication No. 305098916) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Li, X. (2016). An overview on Russian émigré literature in Shanghai. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 9(2), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40647-015-0115-6

Zemleprokhodets [Zemleprokhodets]. (2014). In S. A. Kuznetsov (Ed.), Bol'shoi tolkovyi slovar' russkogo yazyka (Original work published 1998). http://gramota.ru/slovari/dic/?bts=x&word=землепроходец