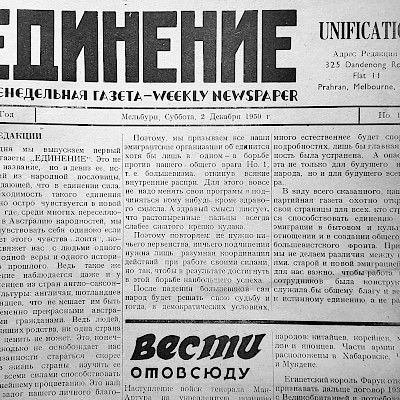

Лиза Иванова написала свои заметки о жизни русской общины Австралии для журнала в Нью-Йорке и любезно предложила опубликовать его в "Единении". Статья написана на английском языке.

Life with the Russian Émigré Community of Australia

Liza Ivanov

Elizabeth Ivanov is a recipient of the Stephen Cohen Fellowship. She teaches Russian in Sydney, Australia.

When I married a Russian Australian and moved to Sydney in 2019, my family friends shook their heads, as if to say, “Here we go, another one of our girls lost to the Village.”

I grew up in New York, bred by its strong Russian White Émigré community, which consists primarily of descendants of White Army soldiers who left Russia in the 1920s after their defeat by Soviet communists. The patriarchs and matriarchs of our community bequeathed us their morals, mannerisms, and, sometimes, a sneaking snobbishness. Many of them came from aristocratic backgrounds; in Russia, they were highly educated and multilingual. Their coats of arms still hang in our living rooms.

Their emigration to the US spanned years, even generations. Our great-grandparents made their way through Europe, evading the Red Army, finding and losing friends, in search of a permanent place to stay. During their travels, they often found spouses of various nationalities (German, Czech, French, etc), who, nevertheless, had to agree to two things: teaching the children the Russian language and baptizing them into the Orthodox Church.

Three generations later, we often still refer to ourselves as zarubezhniki, or, “those beyond the border”.

Across the Pacific ocean lies another part of the family–– the Australian zarubezhniki. The relation between the American and Australian communities is a deep one, rooted at the core of the White Émigré community and Church. Since the 1950s, most émigré spiritual leaders in the worldwide community have received their theological education in a seminary in Upstate New York.

In our world, the boundaries between the continents are fluid. People move for careers or spiritual duties, and, of course, there are transpacific marriages. Some zarubezhnik clans are split in half by those 9 million miles of ocean.

Australian youth regularly flies to the East Coast to visit American relatives or attend the conferences, balls and music concerts. Whenever and wherever youth meet, eyes sparkle and the romancing begins.

The connection that seems like magic––is magic––can be explained easily enough. It is an old revelation: to discover that someone from so far away aligns with you on so many levels, speaks the same languages, and shares both a Western education and an idiosyncratic, nostalgic Russianness from a bygone world.

We studied the same pre-Revolutionary textbooks in our Russian schools, know the same folk songs, attend old-fashioned dances in formal attire and dance to waltzes and folk melodies. And, of course, we are proficient at leading double lives, balancing a “normal” (American or Australian) image among our friends in schools, colleges, and workspaces with our identity in a very active traditional community. We nod our heads as we study Marxist literature in our universities, hiding our rabidly anti-Communist hearts in diplomatic discussion.

So my story was an old story. What I didn’t really understand was that the epitaph of “the village” thrown around by the older generation was not purely stereotype; instead, it hints at the delightful differences that are guarded by the Russian emigres in the Sunburnt Country.

The zarubezhniki I grew up among passed down a quiet but powerful system of etiquette. One must know how to set the table, dress well at church, speak and eat properly, read classics, know the basics of music, drawing, and, preferably, dancing. Of course, far from everyone meets the standard, but everyone is well aware of it.

Australian Russians do not particularly care about such things. In fact, they seem less intense about everything: etiquette, education, even politics. Maybe it is the Australian way –– whether you are a prince or pauper –– you are, en fin, a “mate.”

I began to suspect that something was different at my first feast in Sydney. To my horror, napkins –– which, in my home, had to be carefully folded for every meal –– were nowhere to be found. Instead, boxes of tissues were carelessly slapped down on every table.

As I discovered in time, the history of Russian émigrés in Australia followed a different trajectory than that of their American counterparts. Their route abroad had not taken them through Europe, but through China. For two decades they lived there in relative stability, albeit without passports.

And while the White Émigrés in New York pride themselves on their aristocratic surnames, Russians who arrived in China came from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. There were soldiers who retreated with a faction of the Russian White Army; peasants who simply walked across the border to evade the Communists; and even Russians who traveled to Harbin before the Revolution to build the Chinese Eastern Railway.

In China, the emigres split into two sorts: the “urban” (gorodskie) and the “village” (derevenskie). The “urban” Russians were doctors, engineers, chemists and other specialists. Many occupied high positions in factories and universities in Shanghai, Harbin and other Chinese cities. They prided themselves on their education and expertise.

Meanwhile, the “villagers” and Cossacks settled in an area called Trehrechie, in the basin of three rivers, tributaries of the Argun River. There, they formed villages where they continued their Russian way of life, plowing land and raising cattle. And while urban families usually had smaller families of one to three children, villagers typically could have up to twelve.

In the 1940s, when China embraced communism, and Soviet officials began appearing in Chinese cities. Unease swept through the Russian émigré communities. They began to search actively for ways to leave. The Chinese communist state stripped prosperous villagers of their cattle and land. Russians were actively encouraged to return to their homeland, but few did so. From the 1940 to the 1960s, Russians disappeared from China. Some went to the U.S., others to South America, but the largest proportion moved to Australia.

There, they built their communities up all over again, bringing with them the Russian ways they salvaged, as well as the changes that China had wrought on their way of life. Many of those who lived in cities spoke Mandarin and Cantonese. The generation born in China even looked different, as some émigrés had found Chinese spouses.

The distinction between “urban” and “village” families remained, and churches organized along those boundaries. In a country from which Europe, America and Russia are over twenty hours away by plane, change comes slowly. The country’s small population is focused on a few focal points, and in the white émigré community, everyone knows everyone.

In Australia, I have learned to assume that everyone is related in one way or another. The village families from Trehrechie, in particular, have grown into large clans with family networks that are impossible to untangle, especially for a newcomer.

Australian Russians have kept traditions alive that have disappeared, or, perhaps, never even existed in America. They host glorious feasts. Soy sauce is used abundantly in traditional Russian dishes. Even pel’meni (Russian dumplings) are eaten with soy sauce and sour cream. Pirozhki are made with rice noodles instead of plain rice. And among the village families, weddings do not end on the first night.

The first day tends to pay homage to Western culture: bridesmaids, rehearsed speeches, shiny presents, first dance, cake cutting, and all. The “Second Day,” however, taps deep into village roots. It is the day on which the community tests how well the newlyweds are able to host guests.

The bride and groom don aprons and prepare soup for the guests. The guests do not make the job easy. They try to sabotage the cooking by adding extra salt or pepper. As the couple starts handing out servings, they continue to tease them, clamouring: “Moloduha (young married woman, usually peasant), SOUP!” When they receive their portions, they sneak money to the newlyweds, or use it to bribe them for more soup.

Some time later, the guests start throwing trash on the floor. Though traditionally real garbage was used, modern guests toss wads of newspaper clippings onto the floor. The bride and groom then pick up the trash to showcase their cleaning abilities. As the couple cleans, the guests toss cash onto that ground to compensate the couple for their efforts. Those who are especially cheeky toss coins, to ensure that the newlyweds truly work for their rewards.

As the feast simmers down and guests begin to disperse, the bride and groom continue to work, feeding the latecomers and cleaning the kitchen. Soon, however, evening will come and normal “Western” life will resume. The honeymoon starts the next day. The newlyweds have proven that they are brilliant hosts, as were their parents, and their grandparents.

For that is an area where Australian émigrés have no rivals: hosting with lighthearted Aussie humor, intense Russian generosity, and some soy sauce mixed into the bargain.

Источник: https://jordanrussiacenter.org/news/life-with-the-russian-emigre-community-of-australia